The practice of attempting to replicate historical analogue music equipment within the digital domain remains a popular and enduring trend. Some notable examples would include electric guitar tone studios, or digital amplifier simulators, virtual synthesisers and effects plugins for digital audio workstations such as Logic, GarageBand or Cubase.

As expected, such examples attempt to replicate the much-loved nuances of their analogue counterparts, whether that be the warmth of vintage valve amplification and magnetic tape saturation, or the unpredictable, imperfect and organic characteristics of hand-assembled and aged electronic circuitry.

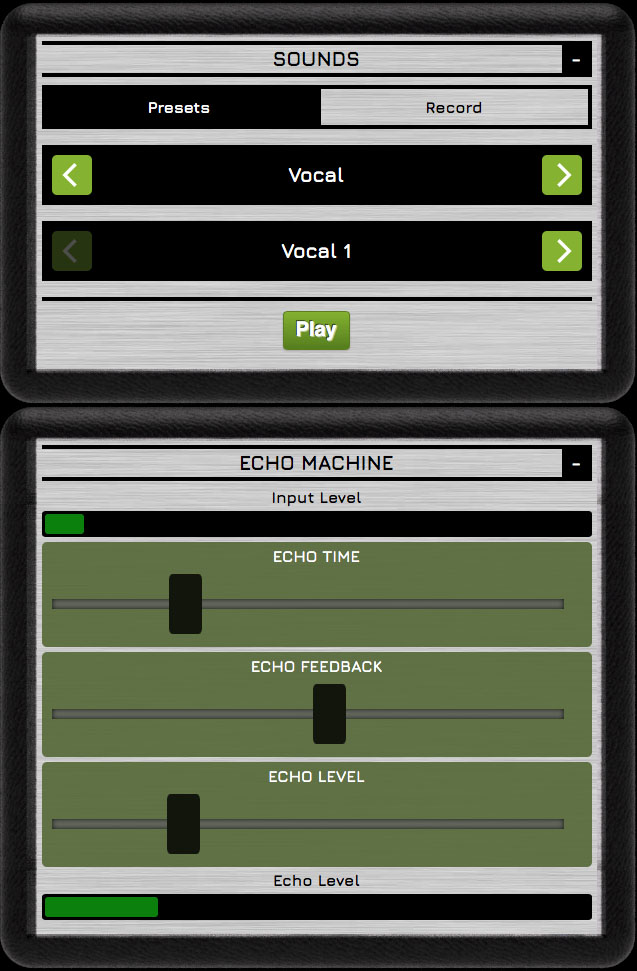

Within the Sonic Futures online interactive exhibits we can hear the sonic artefacts of these hardware related characteristics presented to us within the digital domain of the web; the sudden crackle and hiss of a sound postcard beginning to play and the array of fantastic sounds that can be achieved with Nina Richards’ Echo Machine. After all, who would be without that multi-frequency, whooping gurgle sound you can create by rapidly adjusting the echo time during playback?

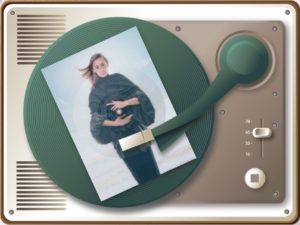

Within digital music technology, while this appetite for sonic nostalgia is interesting in itself, we can also see how this desire to digitally replicate an ‘authentic experience’ extends to the way in which these devices are visually represented, and how the musician, music producer or listener is directed to interact with them. Again, we see this in the Sonic Futures online interactive exhibits: the Sound Postcard Player with a visual design reminiscent of a 1950s portable record player; the Echo Machine’s visual appearance drawing upon the design of Roland’s seminal tape-based echo machine of the 1970s, the RE-201 or Space Echo; and Photophonic with its use of retro sci-fi inspired fonts and illustrations.

We can see even more acute examples of this within some of the other examples given earlier, such as virtual synthesisers and virtual guitar amplifiers, where features such as backlit VU meters (a staple of vintage recording studio equipment) along with patches of rust, paint chips, glowing valves, rotatable knobs, flickable switches and pushable buttons are often included and presented to us in a historically convincing way as an interface through which these devices are to be used.

This type of user-interface design is often referred to as skeuomorphism, and is prevalent within lots of digital environments; the trash icon on your computer’s desktop is a good example (and is often accompanied by the sound of a piece of crunched-up paper hitting the side of metallic bin). Skeuomorphism as a design-style tends to go in and out of fashion. You may perhaps notice the look and feel of your smartphone’s calculator changing through the course of various software updates from one that is to a lesser or greater degree skeuomorphic, to one that is more minimalist and graphical and often referred to as being of a flat design.

Of course, it is only fitting that the Sonic Futures virtual online exhibits seek to sonically and visually reflect the historical music technologies and periods with which they are so closely associated. At a point in time when we are all seeking to create authentic or realistic experiences within the digital domain, whether it be a virtual work meeting or a virtual social meetup with friends and relatives, using the visual and sonic cues of our physical realities within the digital domain reassures us and gives our experience a sense of authenticity.

Along with the perceived sonic authority of original hardware, another notable reason why skeuomorphic design has been so persistent within digital music technology can be explained by the interface heavy environment of the more traditional hardware-based music studio (think of the classic image of the music producer sitting behind a large mixing console with a vast array of faders, buttons, switches dials and level meters). When moving from this physical studio environment to a digital one, in order to facilitate learning, it made sense to make this new digital environment a familiar one.

Another possible contributing factor is the relative ease with which the digital versions can be put to use within modern music recording and producing environments: costing a fraction of the hardware versions and taking up no physical space, they can be pressed into action within bedroom studios across the globe. Perhaps this increased level of accessibility generates a self-perpetuating reverence for the original piece of hardware, which is inevitably expensive and hard to obtain, and therefore its visual representation within a digital environment serves as a desirable feature, an authenticating nod to an analogue ancestor.

There are, of course, exceptions to the rule. The digital audio workstation Ableton Live (along with some other DAWs and plugins) almost fully embraces a flat design aesthetic. This perhaps begs the question: what role, if any, does the realistic visual rendering of a piece of audio hardware play in its digital counterpart? What does it offer beyond the quality of the audio reproduction? From the perspective of a digital native (someone who has grown up in the digital age) its function as a way to communicate authenticity is thrown further into question and perhaps it is skeuomorphic design’s potential to communicate the history behind the technology that comes into focus.

Visit Echo, Sound Postcards and Photophonic to try the online experiments for yourself. You can also read more about the Sonic Futures project.

–originally posted on National Science and Media Museum Blog