post by Phuong Anh (Violet) Nguyen (2022 cohort)

I began my placement in the Data Science team of the Analytic Directorate at the Department of Transport in April 2023 to gain access to datasets for my pilot research. However, I feel that my internship officially began in July, when I was able to become familiar with my work and knew precisely what was expected of me. I still remember the rainy afternoon when I went to the warehouse to collect my IT kit. It was quite a funny memory, and now it is quite emotional to pack and return my kit as my internship is over.

My project

My internship was an integral component of my doctoral research on “Using personas in transport policymaking.” I aimed to combine various data sources to investigate the travel behaviour of various demographic groups, and then use this understanding to inform transport planning and policy formulation.

I began by examining multiple DfT data sources, including the National Transport Survey, Telecoms Data, and Transport Data dashboard. I arranged meetings with several data team members to ask them about how they analysed these data in previous projects. I also had opportunities to discuss with members of other teams including System Thinking, Policy, Social Research, and Data administration… to learn about their work and the policy-making process at DfT.

Since the official release of the transport user personas report in July, I have collaborated closely with the personas team. I began with an examination of the methodology for developing personas. I also attempted to apply additional data science techniques to the same dataset (National Transport Survey) to cluster travellers into distinct groups and compare the results of the various methods.

DfT published transport user personas. (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/transport-user-personas-understanding-different-users-and-their-needs).

I worked with the Social Research team to organise workshops introducing the potential of using personas in DfT’s work, such as Road Investment, AI Strategy, and Highway… In addition, as part of my research, I utilised the Social-technical framework theory to structure the transport system and then gathered data to present and analyse the interaction between personas and other transport system components. On the other hand, I learned how policy is formulated and I will continue to work with the Policy team to investigate how personas can support their work.

Some lessons for myself

About work

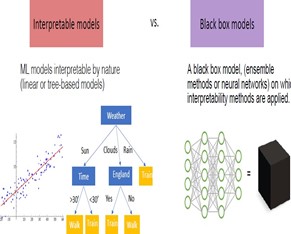

Working on the Data Science team, which is part of the Advanced Analytics Directorate, was an excellent opportunity for me to improve my statistics, mathematics, and programming skills. Colleagues were very knowledgeable and supportive. Through the team’s regular meetings and project summaries, I got a general understanding of which projects are active and which models and methodologies are used to solve the problems. Sometimes I found myself bewildered by mathematical formulas and technical models. Although I have studied Data Science in the past, which has provided me with a foundation in Data analysis and Programming, in real work data looked more complicated. The assignments in the placement have taught me how to overcome the challenges of dealing with multiple data types.

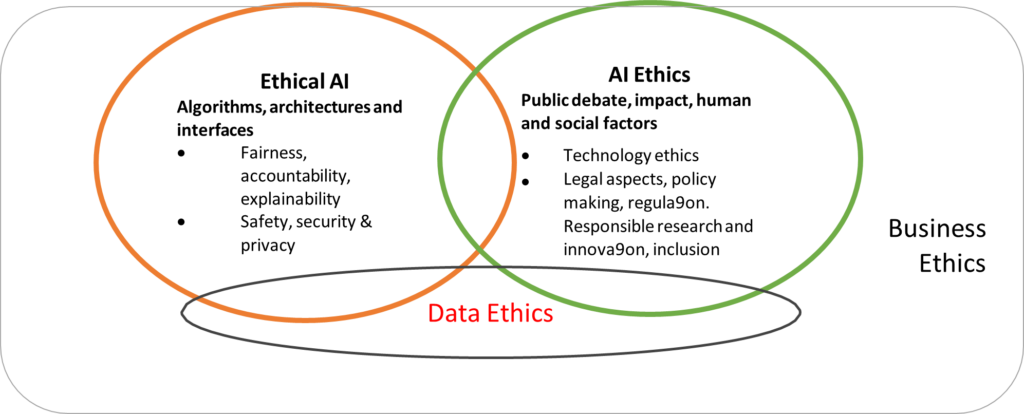

Working in Civil Service, I had access to numerous training resources, workshops, and presentations, including but not limited to Science and Programming, this course covered user-centric services, artificial intelligence, evidence-based policymaking, and management skills. This is why I regard my civil servant account to be so valuable.

I received numerous perspectives and comments on my research proposal thanks to weekly discussions with my line manager and multiple team members. Importantly, I learned how to present and explain my ideas and academic theories to people from diverse backgrounds, as well as how to make the ideas clear and simple to comprehend. I believe this is a crucial skill in multidisciplinary research, communication, and public engagement.

About working environment

This was also my first time working in civil service, a “very British” working environment. Even though I have more than five years of experience in the airline industry, it took me a while to become accustomed to office work. It could be because the working environment in Vietnam differs from that in the United Kingdom, business differs from civil service, and full-time office work differs from hybrid work.

In addition to the knowledge and expertise I gained, I learned a great deal about time management and how to use Outlook professionally to organise my work, as well as how to spend concentration time between multiple meetings every day. This was extremely helpful when having to divide my time between multiple tasks, such as PhD research, placement, and meetings with supervisors from various institutions. In addition, I believe that working in person in the office is more beneficial than remote working, having access to a larger screen. being able to meet and discuss with multiple people, rather than being limited to 30-minute meetings and a small laptop screen. Thus, I travelled to London every week. These regular catchups with my line manager/industry partner proved helpful because the industry partner was able to provide a realistic perspective and I was able to update them on my work and interact with other DfT employees who supported my research.

About my personal development

Since I began my PhD journey, I have experienced many “first-time experiences”, including my first time working in Civil Service. This placement is not only an integral part of my PhD research, but also provides me with a great deal of experience and lessons for my personal growth. It was so unusual and sometimes difficult, but it forced me to leave my comfort zone. I was confident in my ability to perform well, having had the previous experience of being an airline strategist in the past, but the new experience of being an intern, learning something new, made me humble and enthusiastic as if I had just started school.

My principal lesson is to simply DO IT, JUST DO IT. I believe that the majority of my depression stems from my tendency to overthink. There were times when I examined the data set and had no idea what to do. I was even afraid to send emails or speak with others. However, when I actually did what I should do – WRITE something and ASK some questions – and I saw results, I realised that that work is simpler than I originally thought. Then I learned that sitting in a state of distress and worrying about the future is ineffective in resolving the issue. I must take action and be diligent to see myself become a little bit better and better every day.

The summer was very short, and most colleagues took vacation time. Honestly, the internship was not “comfortable” in the beginning, but now I believe everything is going well. This placement is also assisting me in developing a clearer plan for my PhD project. I am grateful for the support and lessons I have gained from this opportunity, and I am considering another summer placement next year.