post by Nicholas Tandavanitj (2023 cohort)

Blast Theory is an artist group based in Portslade, near Brighton, that has been making interactive artwork since 1991. I have worked with the group for the last 30 years and am now one of two artists in the group.

Blast Theory has collaborated with the Mixed Reality Lab at Nottingham since 1998, producing a number of interactive artworks and partnering with the lab in research projects. As part of this collaboration, I’ve contributed to several dozen research papers but always as an artist or designer rather than as a researcher.

Having spent a year jumping ship to begin my PhD at Nottingham, my placement back at Blast Theory was a useful moment to reflect on some of the parallels and differences between working as a PhD researcher and working at Blast Theory.

Creative research at Blast Theory approaches subjects from multiple perspectives – and at pace! Whereas my PhD has involved learning a slower, more methodical approach to reading and learning, at Blast Theory everything – from personally significant anecdotes to pop-culture references and reflections about colour – can compete to carry weight. The process can feel very non-linear. Apparent tangents can reveal themselves as compelling new directions, and part of the process is to allow for these changes without losing momentum.

The focus at Blast Theory is to engage audiences in experiences that prompt critical reflection. This focus creates some very clear priorities – about how it organises processes and how it regards success. While the subjects of Blast Theory experiences are often related to technology, and may involve novel technical development, the projects are not technical ‘demonstrators’ and involve a number of demands besides hitting technical milestones. Ideally, there’s time to practice: to act out the rhythm of the experience, to clarify the voice of the script, to modulate the tone of the performance or to re-work the aesthetics of the screen designs. And then – because it’s ultimately about the substance of the audience experience itself – to test this: to learn what ‘works’ with audiences and what doesn’t. This includes thinking about inclusion and working with diverse test audiences.

There’s a lot in this testing process that Blast Theory have learned from collaborating with HCI researchers. However – unlike more formal research studies – this testing can also be ad-hoc, gathering feedback with different levels of formality through conversations as well as through fully-fledged user tests. It also tends to be more instrumental, prioritising how to shape the experience to meet immediate artistic needs over answering long-held research questions, or focusing on pragmatic issues such as accessibility or support across older devices.

There’s normally an immovable public launch date and not enough time or money to do everything, so the process as a whole is about doing things with urgency, coming up with shortcuts, looking for easy wins, deciding on where to compromise and where to spend your effort.

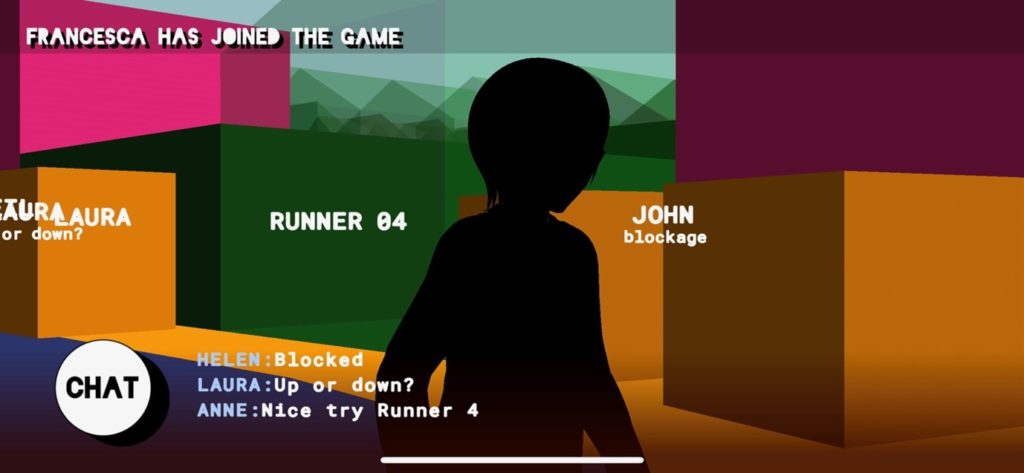

The focus of my placement at Blast Theory was remaking a mixed reality game project called Can You See Me Now? originally developed in 2001. This meant many of the steps for creative development were skipped, taking the project forward to production and testing. This work started with writing a functional specification for the game and assisting in recruiting developers. By good luck, we managed to engage Ben Neal (a creative technologist at Nottingham’s VIP studios) and John Sear (a “real-world game” developer based in Birmingham) to help deliver the project.

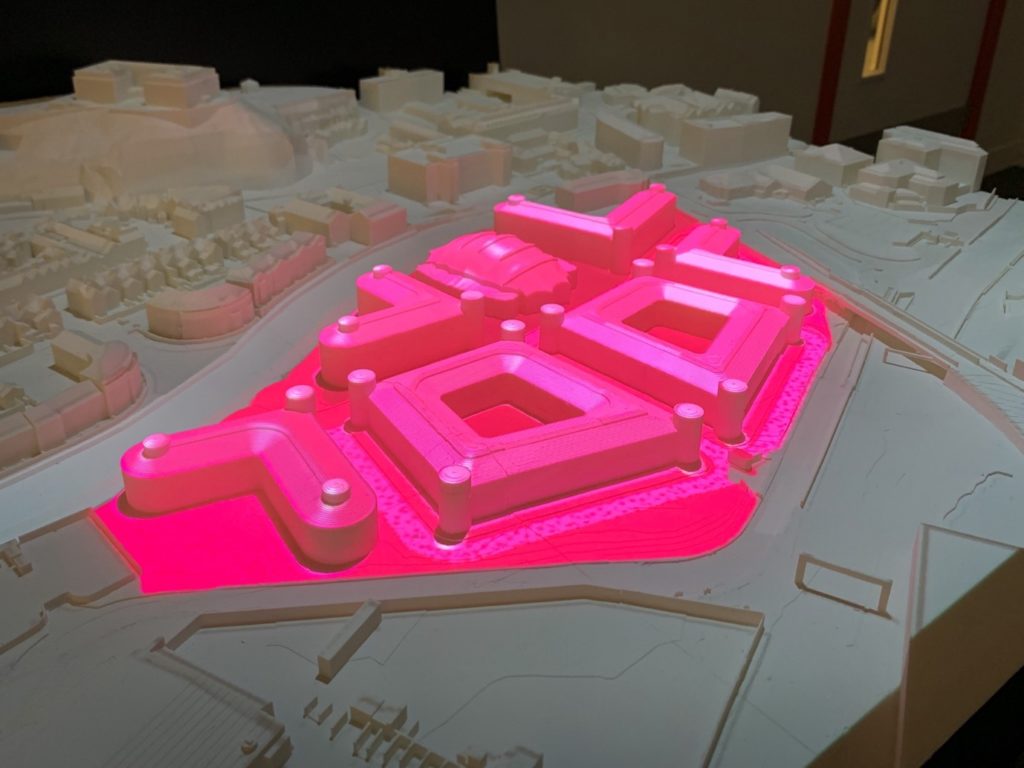

Over the course of the placement, I helped in a Kickstarter campaign to fundraise for the work, developed screen designs for the app, created and reviewed software milestones, set-up the click-through tests that are Blast Theory’s budget version of software ‘quality assurance’ and took part in a number of audience focused game tests. These concluded with a public launch at the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts in November, and a workshop this February hosted by City As Lab at Castle Meadow Campus that integrated Gary Priestnall’s PARM as a spectator interface.

Along the way, I managed to return to one of my favourite activities of the last twenty years: making 3D models for game environments. I learned a lot – possibly more than I wanted to – about building and deploying Unity projects to Apple App Store and Google Play. I also learned just how many days of admin and compliance work it now takes to publish an app. Being back at Blast Theory, I was reminded how much momentum comes from being in a small production team that is focused on delivering an experience for the public. It’s exciting, but I’m happy to have stepped back to my PhD.

While there’s some overlaps with Can You See Me Now? in my research – in thinking about how mixed-reality can ‘thicken’ our sense of place – the main thing that I bring back is an appreciation of the spaciousness of paying attention in lots of directions at once – to ideas, to different artists’ practices and to new possibilities with technology. I can see one of Steve Benford’s diagrams of threads of parallel activity in my head – and while I know this has to land somewhere, the combination of reading, practice and exploring in data seems an unaccountable luxury for the moment.