post by Yang Bong (2021 cohort)

Introduction: Placement Overview

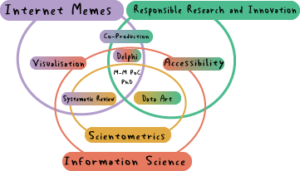

In the summer of 2023, I had the privilege of working as a Visiting Fellow at the University of Technology Sarawak (UTS) in Sibu, Malaysia. This three-month placement, hosted by Dr. Tariq Zaman at the Advanced Centre for Sustainable Socio-Economic and Technological Development (ASSET), aligned directly with my PhD research on digital inclusion with Indigenous communities, which was a core research interest of ASSET.

ASSET’s focus on ICT for development (ICT4D) in Sarawak provided a unique context to apply my research on human-computer interaction (HCI) and digital marketplaces for rural microenterprises in real-world settings. As part of the optional placement module under my doctoral training, the placement was generously supported by the Horizon Centre for Doctoral Training (CDT).

Initial Expectations and Goals

As a PhD candidate with a research interest in digital inclusivity in developing economies, my initial anticipation of this placement was that it would provide access to local stakeholders and communities. The hope was that interacting with local communities would enhance my understanding of how local cultures interact with digital technologies.

ASSET’s work in ICT4D and HCI within Indigenous communities aligned very well with my PhD in creating inclusive digital platforms for rural microenterprises. Through the placement, I aimed to gain insights into designing technology that respects and reflects the values, needs, and infrastructure of Sarawak’s rural communities. My goals included learning from established academics in the field, expanding my local network for data collection, and exploring community-based research models. I also approached the placement with an open mind, knowing that some aspects of the experience, such as connections with specific stakeholders, would unfold organically.

Core Activities and Responsibilities

During my time at UTS, I led a short-term project as a Visiting Fellow at UTS, in partnership with the Sarawak Development Institute (SDI). The project focused on mapping the digital entrepreneurship ecosystem in Sarawak. The aim was to map out the then multi-fold, often seemingly repetitive efforts in digitalising entrepreneurship across different stakeholders in Sarawak. The work involved leading a team of researchers through a desk study, followed by the conducting of interviews with key stakeholders across the region. This research, which has since been submitted to a journal, gave me invaluable insights into the local digital entrepreneurship landscape.

Alongside this project, I was also the internal communication chair for the ACM conference: Participatory Design Conference, held in Sarawak. Responsibilities included organising meetings, finalising conference schedules, and scouting suitable venues with the organising committee in and around Sibu. Through these activities, I had the opportunity to engage with a broad network of stakeholders: including local councils, government agencies, research institutions, and local entrepreneurs, all of which significantly expanded my understanding of Sarawak’s digital entrepreneurship scene.

Adapting My Skills to the Placement Environment

The placement provided a platform to enhance and re-orient several of my academic and professional skills. First, my communication skills were improved, particularly in engaging with stakeholders from varied backgrounds, from city council officials to rural entrepreneurs. It also helped me refine my Malay language skills, essential for rapport building and further fieldwork. Additionally, leading a multi-stakeholder project honed my project management skills, where I have gained confidence in both leading and coordinating research with senior academics and research institutions: from proposal writing to weekly catch-ups and finally, publication. Lastly, my academic writing skills were also strengthened. As I took the lead on writing the research paper, the experience not only built my confidence for my PhD thesis writing but also better prepared me to undertake similar projects in the future.

Key Lessons and Future Impact

Spending three months in Sibu immersed me in Sarawak’s local culture and work environment, offering firsthand insights into local perceptions of digitalisation, digital platforms and digital entrepreneurship, all instrumental to the findings of my PhD.

This experience has improved my understanding of not just the local perspectives of digital platforms, it has also expanded my vision for both research and professional possibilities within the region in the future. Beyond professional skills, this placement taught me to embrace new opportunities and approach uncertainties with courage. From an initial blind email to Dr. Tariq Zaman via Google Scholar, to signing a Memorandum of Understanding between our respective institutions, this experience has taught me the value of taking bold steps and trusting the process, even when the present path may seem uncertain.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Tariq Zaman for his generosity and support throughout the attachment, and for his wisdom and guidance in the many conversations we have had the pleasure of. My gratitude also goes to Dr Gary Loh, Dr Ghazalam Tabussum of ASSET, Dr Kok Leong Yuen and the wider team at the Sarawak Development Institute, who worked on the mapping research project together. To the community partners in Bawang Assan, especially Marcathy Gindau and Stanley Marcathy, thank you for partnering and supporting the various research projects conducted in the community.

Lastly, a huge thank you to the Horizon CDT for financially supporting the whole of my placement in Sarawak.