Experiences of an Early(ish) Adopter in the Algarve

post by Charlotte Lenton ( 2020 cohort)

The Algarve is a tourist destination located on the south coast of Portugal which is incredibly popular with tourists from across Europe including the UK. The area is famous for the guaranteed sunshine, sandy beaches, and welcoming hospitality. According to Statista (2023) the region received almost 4.8 million tourists in 2022, close to pre-pandemic figures. Popular resort areas include Albufeira, Lagoa, Carvoeiro, and Vilamoura. The latter is the place I am currently calling home for the next couple of months – Picture of the villa I have ended up in below (long story with a lot of complications and incredibly stressful moments involving several accommodation providers letting us down but it turned out well in the end bagging a massive villa with pool!).

I have visited the Algarve many times with my family whilst growing up and it was actually the first abroad destination I travelled to on holiday with my husband over ten years ago. It’s safe to say that the destination has a special place in my heart. But due to the pandemic and our finances being used to renovate our house for the past couple of years, my university exchange visit would be my first time back in the Algarve for almost seven years!

Those of you that know my PhD research area will know that I am most interested in exploring the impact that the digital tourism environment has on tourist mobility, accessibility, and experience for people who do not or are not able to use digital technology for whatever reason. I believe that being a ‘late adopter’ of technology is an ever-changing and evolving factor of people’s lives as we all make decisions about what technology we want to use, why we use it, and also why we choose not to use it sometimes. This will depend on the technology of course, someone might want to use a smartphone application to help them to travel by train if they are a frequent user of the railways. Likewise, they might also decide they do not want to have a digital ticket on their smartphone when travelling by plane as they are concerned the battery might run flat and feel more ‘secure’ with a printed version of the boarding pass. So, you can see how the extent to which an individual is a late or early adopter of technology can vary a lot between different technologies, the travel situation, and their personal circumstances. I consider myself to be on the early adopter side of the spectrum for most things like smartphones, but also a late adopter of many other innovations that I am more sceptical of.

There’s also a lot of research available that has explored destinations in terms of their ability, willingness, and innovativeness to adopt and use new technologies (see Buhalis and Deimezi, 2004; Spencer et al., 2012; Collado-Agudo et al., 2023) . This isn’t my research area as I am more interested in individual passengers and tourists, but nevertheless it is an interesting topic. Again, the technologies adopted at destinations vary between countries, regions, and businesses. Generally, lots of destinations in Europe have adopted technologies such as card and contactless payments as this has been widely available for a number of years. I raise this point as this has been an area of considerable challenge for me since arriving in the Algarve a couple of weeks ago.

When I am at home or travelling domestically within the UK, I hardly ever use cash nowadays. In fact, I find myself asking businesses if they accept cash as many places like restaurants, bars, and cafes only accept contactless or card payments. This move to a cashless society seems to have picked up pace since the pandemic in the UK. Admittedly, since the pandemic, I haven’t actually travelled outside of the UK until now, but I assumed (wrongly) that other countries in Europe were also following suit with fewer establishments accepting cash. In preparation for my travel, I took out a fee-free credit card and a new bank account which would also allow me to use the debit card abroad without incurring any fees. In my naivety, I thought that 100 euros in cash would be more than enough to see me through eight weeks abroad as ‘everywhere takes card nowadays’…. I wonder how many other British tourists have the same mindset as me in this regard?!

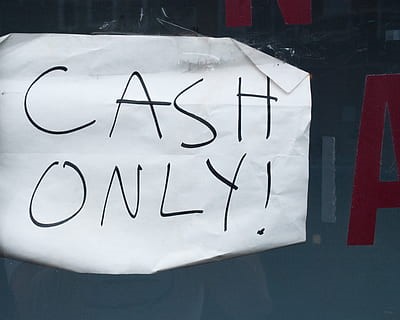

Upon arriving in the Algarve, I realised that I had made a terrible mistake in not bringing more cash with me as I encountered a number of places that only accept cash within the first few days. In addition to bars and cafes that only accept cash, there were also cash-only car parking machines! Coming from a country where several councils are moving their parking charges to ‘app only’ payments I couldn’t believe that the car parking machines here did not even accept contactless card payments.

A few days later it was time for my first visit to the Universidade do Algarve for a tour, to see my office, and have lunch with some colleagues. As my bag was heavy, I decided to leave it in my office and just take my phone with me… after all I have Apple Pay on my phone so why on earth would I need my purse?! (You see where I am going with this!) On arrival at the university canteen, I ordered the chicken dish for lunch with the help of my lovely Portuguese colleagues to translate this for me! When we got to the till to pay, I noticed that everyone else was inserting their bank card into the machine and realised that the machine was not contactless. Luckily my colleague and friend Professor Dora paid for my lunch as I explained that I was intending to use Apple Pay. This was not the end of the card payment saga for me at the university though… A couple of days later I attended an event which was followed by a self-paying lunch in the much fancier university restaurant. I made sure that I had my purse with me on this occasion so I could pay using my credit or debit card. On presenting myself at the till to pay for my food the staff member looked at my credit card, and told me it was a foreign card so was not accepted by the university so I would have to pay cash. I tried to reason with her by saying that it would be accepted as it would pay in Euros, it was a Mastercard, etc. but she was having none of it. So, for now, at least, it appears that I will need to pay in cash for my meals at the university too.

I guess my point here is surely I cannot be alone in my approach with assuming that European popular tourist destinations, like the Algarve, would be as keen to move to a cashless society as the UK. I am not saying that I agree with the UK moving to a cashless society, as I do think this will have negative consequences for many people including those whom my research focuses on giving voice to. But as a tourist who is so used to using contactless cards and Apple Pay in UK daily life, I wonder how many other Brits are caught out by this and end up using cash points (ATMs) with appalling exchange rates to get by when abroad. Maybe the tourists who are later adopters of this sort of thing would in fact be better prepared for travelling to the Algarve as they may prefer to use cash, who knows?! In any case, I am lucky that my parents are coming out to visit me this weekend, so I have asked them to exchange more cash at home where there’s a decent exchange rate and bring it out to me!