post by Phuong Anh (Violet) Nguyen (2022 cohort)

Following my annual progression review in mid-June, I attended the ESRC Digital Good Network Summer School at The University of Sheffield. It was a nice event to conclude my second year.

Introduction to Digital Social Good Network and the Summer School

The Digital Good Network is a research program that is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) UKRI. It brings together scholars from several disciplines to explore the characteristics of an ideal digital society and the steps needed to achieve it. The Digital Good Network Summer School offers fully funded participation to PhD researchers, enabling them to explore a variety of theoretical, methodological, and professional development subjects related to the digital good. The program provided a revelatory experience that emphasized the significance of redirecting our attention from just dealing with digital harms to actively striving for digital benefits, guaranteeing favourable results of digital technologies for both individuals and communities. In addition to the lectures, workshops, and sprints focused on the Digital Good Topic, we also acquire valuable skills for early career researchers, including grant writing, understanding the significance of engaging with stakeholders from various sectors in a research-transforming manner and receiving insights from esteemed editors of digital society journals on writing exceptional peer-reviewed articles.

The Summer school activities

On the first day, the program commenced with introductory activities and an ice-breaker game. Then, during the Pecha Kucha session, every participant delivered a concise 2-minute presentation of their study, which was then followed by opportunities for networking and engaging in discussions on subjects of mutual interest. In the afternoon, we had an interdisciplinary reading session centred on pre-read papers. During this session, we examined how various disciplines, as represented in these papers, perceive the capabilities and constraints of technology in advancing ‘the good.’ Additionally, we explored the commonalities and disparities among these perspectives and considered how the insights gained from these disciplinary viewpoints can be applied to our own research. This was the most enjoyable aspect of my day. Afterwards, we participated in the ‘Off-key note’ panel called ‘The Good in Digital Good,’ which discussed topics such as labour, charity, creativity, global flows, harm, and power. The recording of the ‘off-key note’ panel session can be accessed via this link https://digitalgood.net/the-good-in-digital-good-an-off-key-note-session-of-the-digital-good-network-summer-school-2024/

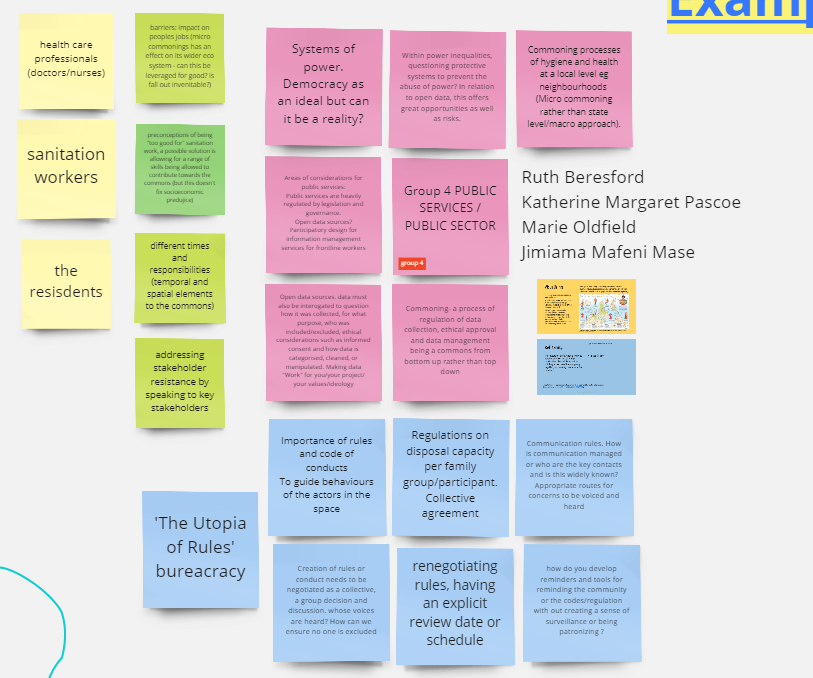

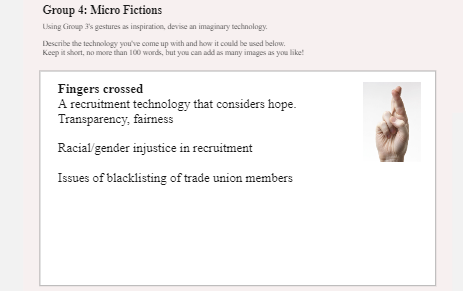

On the second day, we examined the impact of design thinking on enhancing digital products and participated in a competition to create and develop our ideas in teams.

On the third day, we dedicated our attention to skill enhancement. We explored the essential components of a robust publication in various fields, examined techniques for conducting effective digital research, analyzed the advantages and obstacles of employing ChatGPT for evaluating academic studies, and explored creative methods for enhancing our curriculum vitae as doctoral candidates.

My experience in the Summer School

The three-day Summer School was both intensive and enlightening, packed with knowledge that broadened my understanding of various methodologies across disciplines. We also collaborated in teams to design provocative prototypes for digital good during the workshop.

Since starting my PhD at Horizon CDT, I have attended several networking events. In my first year, most of these events were centred around PhD students in Computer Science, leading to highly technical conversations. However, in my second year, as I began working within the Human Factors Research Group, the topics became more aligned with my research, resulting in more focused discussions. During the Summer School, most participants were social science researchers, particularly in psychology, which I found to be a mind-opening experience. Although we all shared a common goal of advancing digital good—particularly in areas like sustainability, equity, and resilience—the diverse perspectives and approaches from different disciplines sparked provoking, engaging and enriching debates encouraging me to reflect on my research.

Sheffield is a charming city, and I arrived early to join other participants for a day trip to the Peak District. It was wonderful how we were able to form a close-knit, friendly group in just three days together which supported each other in PhD life. Participating in summer school requires the utilization of several skills, such as presentation, debate, teamwork as well as how to make meaningful connections. I am happy with my accomplishment.

What I can take for my own

The contribution of design thinking to the Digital good and Unintended by design

Prior to proposing any novel concept or suggestion to people, it is essential to comprehend their needs. The value of design thinking in the realm of digital products is derived from its emphasis on a problem-solving strategy that is oriented around the needs and experiences of humans. Design thinking prioritizes the needs, behaviours, and experiences of individuals, allowing for the creation of digital solutions that are both inventive and ethical. These solutions are also inclusive and capable of addressing social concerns. This aspect is really congruent with my studies.

Nevertheless, there may be unintended or inadvertent consequences that arise from activities that the designers cannot anticipate or acknowledge throughout their work. While conducting research on policymaking, I have recognized the significant ethical concerns around transparency and accountability in the decision-making process. It implies the necessity for a more thorough analysis of the underlying reasons behind policy choices and the results they generate.

The diverse topic in digital good and methodology to investigate a problem

How to discuss with people who have different disciplines is a skill I learned in the multiple-disciplinary research environment of CDT, which is really helpful for networking and discussion. Digital technology is embedded in almost every aspect of daily life, impacting fields as varied as healthcare, education, economics, and social justice. Because of this widespread influence, the problems and opportunities associated with digital good are complex and multifaceted. For example, during the summer school, there was a “strange” topic: is there any impact of watching cat videos on the internet on mental health”. No single discipline can fully address these challenges; instead, a multidisciplinary approach is essential. Researchers from different fields bring unique perspectives and methodologies that can complement one another, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the issues at hand.

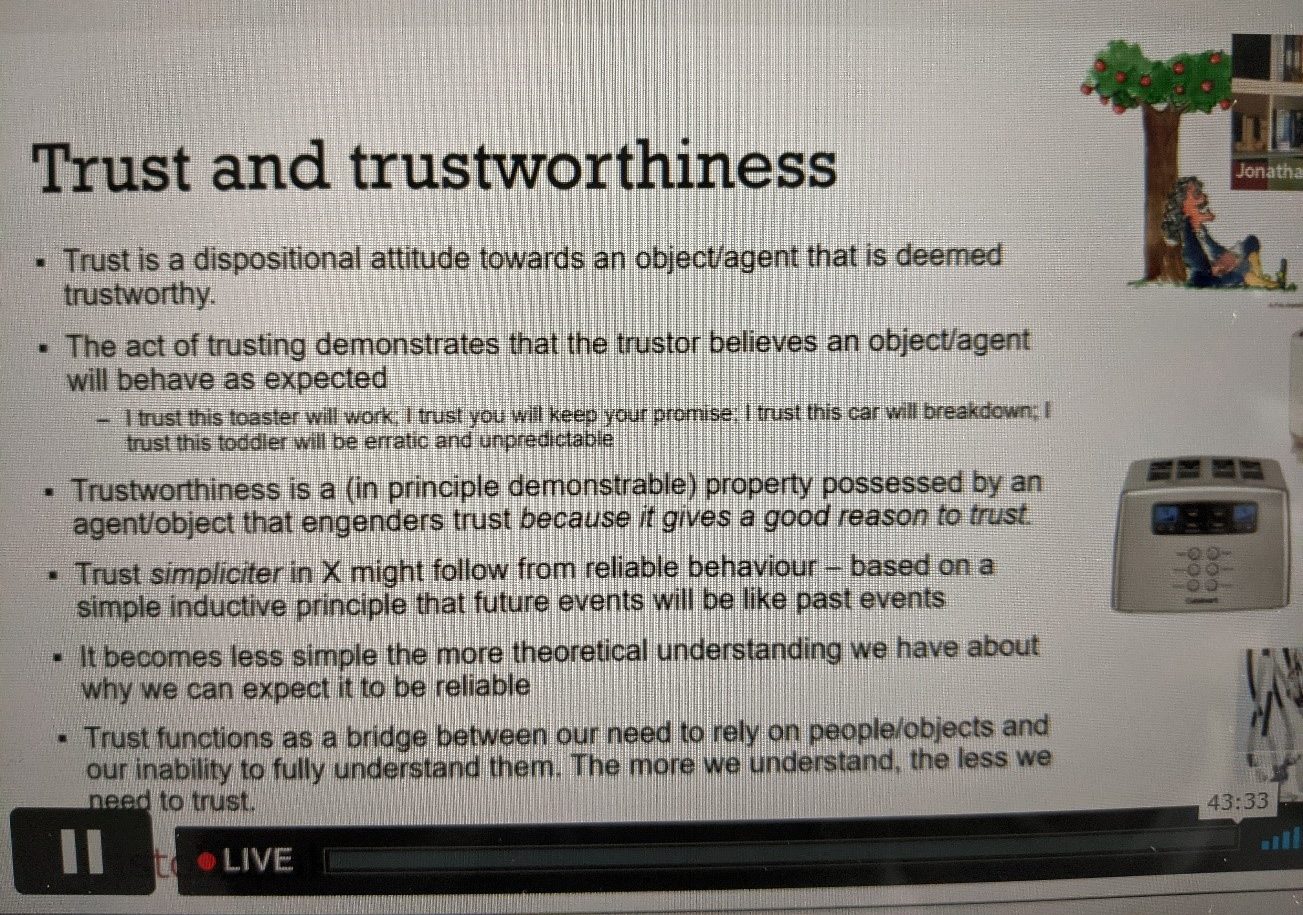

Open mind to join a provoking debate

During summer school, while engaging in discussions regarding various research methodologies, there were several novel methods or initiatives on which I had numerous critiques due to their lack of persuasiveness. However, what I have learned is that new things require time to develop. Criticisms should not solely focus on pointing out shortcomings, but rather offer solutions to improve them. For example, while discussing social media, we often address the impact on mental health and the trustworthiness of relationships formed through these digital platforms. However, it is important to consider that we may also develop a digital platform specifically designed for individuals to find solace and prioritize their overall well-being. By incorporating a wide range of perspectives, we can generate comprehensive and efficient solutions, guaranteeing that digital technologies are designed and implemented in manners that genuinely enhance society. By being open to learning, I will gain greater value for myself.