post by Luke Skarth-Hayley (2018 cohort)

It’s tough to do outreach during a pandemic. What can you do to help communities or communicate your research to the public when it’s all a bit iffy even being in the same room as another person with whom you don’t live?

So, what can we do?

Well, online is obvious. I could certainly have done an online festival or taught folks to code via Zoom or Skype or Teams or something.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve got a serious case of online meeting fatigue. We’re not meant to sit for hours talking in tiny video windows. I’m strongly of the opinion that digital systems are better for asynchronous communications, not instantaneous.

So, what did I do?

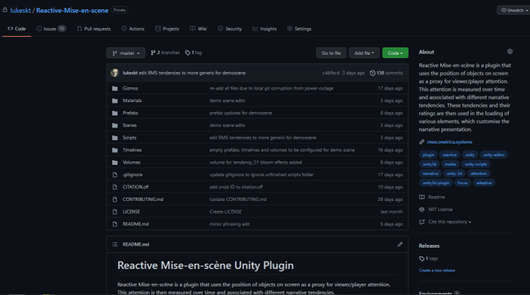

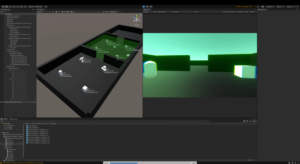

I took my research online, asynchronously, through various means such as releasing my code as an open-source plugin for the Unity game engine and creating tutorial videos for said plugin.

Open-Source Software

What is open source? I’m not going to go into the long and storied history of how folks make software available online for free, but the core of it is that researchers and software developers sometimes want to make the code that forms their software available for free for others to build on, use, and form communities around. A big example of open-source software is the Linux operating system. Linux-based OSes form the foundation on which are built most websites and internet-connected services you use daily. So, sometimes open-source software can have huge impacts.

Anyway, it seems like a great opportunity to give back from my research outputs, right? Just throw my code up somewhere online and tell people and we’re done.

Well, yes and no. Good open-source projects need a lot of work to get them ready. I’m not going to say I have mastered this through my outreach work, but I have learned a lot.

First, where are you going to put your code? I used GitHub in the end, given it is one of the largest sites to find repositories of open-source software. But you might also want to consider GitLab, Source Hut, or many others.

Second, each site tends to have guidance and best practices on how to prepare your repository for the public. In the case of GitHub, when you’ve got research code you want to share, in addition to the code itself you want to:

-

-

- Write a good readme document.

- Decide on an open-source license to use and include it in the repository.

- Create a contribution guide if you want people to contribute to your code.

- Add a CITATION.cff file to help people cite the code correctly in academic writing.

- Get a DOI (https://www.doi.org/) for your code via Zenodo (great guide here: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/citeyourcode) so it can be cited correctly.

- Create more detailed documentation, such as via GitHub’s built-in repository wiki, or via another method such as GitHub pages or another hosted documentation website.

- Bonus: Consider getting a custom domain name to point users to that redirects to your code or that hosts more information.

-

That’s already a lot to consider. I also discovered a couple of other issues along the way:

Academic Code

Academic Code, according to those in industry, is bad. Proving an idea is not the same as implementing it well and robustly, with all the tests and enterprise code separation, etc. That said, I have seen some enterprise code in my time that seems designed to intentionally make the software engineer’s job harder. But there is a grain of truth regarding academic code. My code was (and still is in places) a bit of a hacked together mess. Pushing myself to prepare it for open source immediately focused the mind on places for improvement. Nothing is ever done, but I did find ways to make the code more adaptable and flexible to diverse needs rather than just my own, fixed some outstanding bugs, and even implemented custom editors in Unity so non-programmers would be able to do more with the plugin without having to edit the scripts that underpin it. In addition to making the code better for others, it made it better for me. Funny how we do what’s best for ourselves sometimes under the guise of what’s best for others.

Documenting a Moving Target

No software is ever done. Through trying to break the Curse of Academic Code as above, I rewrote a lot of my plugin. I had already started documenting it though. Cue rewriting things over and over. My advice is split your docs into atomic elements as much as possible, e.g., if using a wiki use one page per component or whatever smallest yet useful element you can divide your system up into for the purposes of communicating its use. Accept you might have to scrap lots and start again. Track changes in your documentation through version control or some other mechanism.

Publicising Your Open-Source Release!

Oh no, the worst bit. You must put your code child out in the world and share it with others. Plenty of potential points to cringe on. I am not one for blatant self-promotion and rankle at the idea of personal brands, etc. Still, needs must, and needs must mean we dive into “Social Media”. I’m fortunate I can lean on the infrastructure provided by the university and the CDT. I can ask for the promotion of my work through official accounts, ask for retweets, etc. But in general, I guess my advice is put it out there, don’t worry too much, be nice to others. If people give you grief or start tearing apart your code, find ways to disambiguate real feedback from plain nastiness. You are also going to get people submitting bug reports and asking for help using your code, so be prepared for how you balance doing some of that with concentrating on your actual research work.

Tutorial Videos

Though I can quite quickly point back to the last section above, and say, “MOVING TARGET!” there is value in video tutorials. Even if you must re-record them as the system changes. For a start, what you see is what you get, or more accurately what you get to do. Showing people at least one workflow with your code and tools in a way that they can recreate is immediate and useful. It can be quick to produce, with a bit of practice, and beats long textual documentation with the occasional picture (though that isn’t without its place). Showing your thinking and uses of the thing can help you see the problems and opportunities, too. Gaps in your system, gaps in your understanding, gaps in how you explain your system are all useful to flag for yourself.

Another nice get is, depending on the platform, you might get an accidental boost to awareness of your work and your code that you’ve released through The Algorithm that drives the platform. Problems with Algorithms aside, ambient attention on your work through recommended videos e.g., on YouTube can be another entry point for people to discover your work and, their attention and interest willing, prompt them to find out more. This can be converted into making contacts from people who might want to use your tools, who might then participate in studies, or it may make people pay attention to your work, which you can use to nudge them into checking out something you are making with your tools, again making them into a viewer/player/potential study participant.

But how do you go about recording these things? Well, let’s unwrap my toolkit. First up, you’re going to need a decent microphone, maybe a webcam too. Depending on how fancy you want to get, you could use a DSLR, but those can be prohibitively expensive. Maybe your research group has one you can borrow? Same goes for the microphone. I can recommend the Blue Yeti USB microphone. It’s a condenser microphone, which means the sound quality is good, but it can pick up room noise quite a bit. I just use a semi-decent webcam with at least 720p resolution, but I’ve had that for years. This is in case you want to put your face on your videos at any point. Just how YouTube do you want to be?

Anyway, you have some audio and maybe video input. You have a computer. Download OBS Studio is my next recommendation. You can get it at https://obsproject.com/. This is a piece of software that you can use to record or stream video from your computer. It even has a “Virtual Camera” function so you can pipe it into video conferencing software like Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Cue me using it to create funny effects on my webcam and weird echoes on my voice. But, in all seriousness, this is a very flexible piece of freely available software that allows you to set up scenes with multiple video and audio inputs that you can then switch between. Think of it as a sort of home broadcasting/recording kit. It is very popular for people making content for platforms like YouTube and Twitch.tv. I’ll leave the details to you to sort out, but you can quite quickly set up a scene where you can switch between your webcam and a capture of your computer’s desktop or a specific application, and then start recording yourself talking through whatever it is you want to explain. For example, in my tutorial videos I set it up so I could walk through using the plugin I created and open-sourced, showing how each part works and how to use the overall system. Equally, if you aren’t confident talking and doing at the same time you could record your video of the actions to perform, and then later record a separate audio track talking through what you are doing in the video. For the audio, you might want to watch the video as you talk and/or read from a script, using something like Audacity, a free tool for audio recording you can download from https://www.audacityteam.org/.

Which brings me on to my next piece of advice. Editing! This is a bit of a stretch goal, as it is more complex than just straight up recording a video of you talking and doing/showing what you want to communicate. You could just re-record until you get a good take. My advice in that case would be to keep each video short to save you a lot of bother. Editing takes a bit more effort but is useful and can be another skill you can pick up and learn the basics of with reasonable effectiveness. Surprisingly, there is some excellent editing software out there that is freely available. My personal recommendation is Davinci Resolve (https://www.blackmagicdesign.com/products/davinciresolve/), which has been used even to edit major film productions such as Spectre, Prometheus, Jason Bourne, and Star Wars: The Last Jedi. It is a serious bit of kit, but totally free. I also found it relatively simple to use after an initial bit of experimentation, and it allowed me to cut out pauses and errors, add in reshot parts, overdub audio, and so on. This enables things like separating recording the actions you are recording from your voiceover explanation. Very useful.

Next Steps

My public engagement is not finished yet. My research actively benefits from it. Next up I intend to recruit local and remote game developers in game jams that use the plugin, specifically to evaluate the opportunities and issues that arise with its use, as well as to build an annotated portfolio as part of my Research through Design-influenced methodology.

Conclusion

So, there you have it. Ways I’ve tried to get my research out to the public, and what I plan to do next. I hope the various approaches I’ve covered here can inspire other PhD students and early-career researchers to try them out. I think some of the best value in most of these comes from asynchronicity, with a bit of planning we can communicate and share various aspects of our research in ways that allow a healthy work-life balance, that can be shaped around our schedules and circumstances. As a parent to a young child, I know I’ve appreciated being able to stay close to home and work flexible hours that allow me to tackle the unexpected while still doing the work. If there is one thing, I want to impress upon you, it is this: make your work work for you, on your terms, even if it involves communicating your work to tens, hundreds, thousands of people or more. Outreach can take any number of forms, as long as you are doing something that gives back to or benefits some part of society beyond academia.

You can get the Unity plugin here: https://github.com/lukeskt/Reactive-Mise-en-scene