post by Harriet Cameron (2018 Cohort)

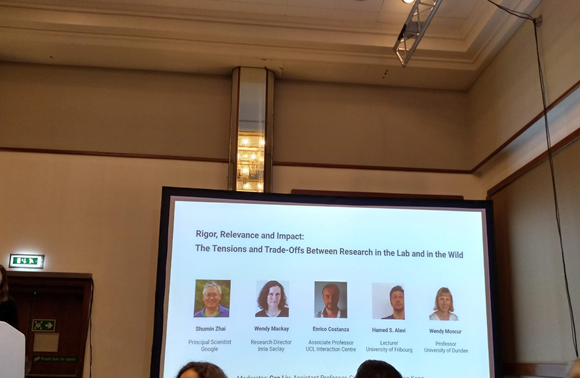

Hiiii everyone, it’s Harriet here. Hope you’re all doing well and finding ways to support yourselves and the folks around you. I’m going to share a few words about my experience of writing and presenting a paper at the Designing Interactive Systems (DIS) conference in this, the year of our undoing, 2020. Now I know you are all sick of reading about this so I’m going to get it out of the way early and then only reference it in thinly veiled metaphors where I absolutely have to. Obviously, when we first had our paper accepted into DIS, we weren’t expecting a pandemic to barrel in and seal off the opportunity to hop over to Eindhoven for the week, present our paper in person, and have a good ol’ chin wag with other researchers about our findings. So this blog post might be a little different given that chunks of it will be dedicated to navigating a virtual conference and the changes that have resulted from that.

So first of all, I’ll start you off with an introduction to the paper. I was a co-author on the paper with a number of other amazing and talented folks – Dr Jocelyn Spence (lead), Dr Dimitri Darzentas, Dr Yitong Huang, Eleanor Beestin, and Prof Steve Benford. It was about a project called VRtefacts [4], something I have written about previously[1]. The TL;DR for VRtefacts is that it was a fantastic project which came about as an offshoot of the GIFT project [2] – a series of international projects funded through Horizon 2020 that look at ways of using gifting to enhance cultural heritage experiences. VRtefacts used a combination of physical props and virtual reality to encourage visitors to a museum to donate personal stories inspired by a small selection of artefacts on display. Our paper explores how the manipulations and transitions embedded in VRtefacts can enable personal interpretation and enhance engagement through performative substitutional reality, as demonstrated through storytelling.

I first joined the squad because my background in human geography offers up a different approach to HCI analysis that can draw out themes of place, space, and identity in novel ways. For this research, we conducted thematic analysis on post-experience interviews and videos of participant stories captured in the deployment. I primarily focused on conducting a section of the analysis to examine how space and place were represented and understood throughout participants’ experiences. Through the different passes conducted for the thematic analysis [1], these loose concepts of space and place evolved into how physical distance and scale affected the experience, and how the transitions between different spaces and places – both physically and emotionally – impacted on the storytelling. At the same time as I was working on this, Jocelyn and Yitong were conducting their thematic analyses on the data to explore other concepts that came up like contextualisation of stories, attitudes towards the objects and the museum, and the influence of touch and visuals.

Working together like this was a really interesting experience. I’m familiar with NVivo [3] – the software widely used for this type of qualitative coding – having used it a few times before in my work. However, finding ways to navigate NVivo as a team – exploring how to compare notes, cross-reference emerging codes, and merge/condense/combine the codes that overlapped – offered a whole new challenge. The version of NVivo we had access to did not allow multi-party editing of one database and we were using different operating systems (which each have their own incompatible versions of the software), so we had to get slightly creative in just how we did team working. After some trial and error, we decided to each work on our own dataset and periodically combine them into one master document. Sometimes this meant having to compare the documents and painstakingly comb through them for wayward spaces and capitalisations just so that we could merge our files – a great joy to be sure. But we also regularly got together and went through our codes side-by-side with the other members of the team, deciding on how best to combine our efforts. By doing so, we essentially added a new kind of ‘pass’ per pass that sure, created extra work, but genuinely helped us to better understand and be able to justify not only our own codes but each other’s as well.

This was an approach that we also extended somewhat to the paper writing itself. We each branched off and wrote our own specialised sections, and then came back together to work on the overall flow and content. Across several iterations of the paper, we worked out what the core findings were and how best to present them, ultimately landing on performative substitutional reality as understood through manipulations (of physicality, visuals, and scale) and transitions (between spaces and through storytelling). On a personal note, it was really validating and exciting to see my contribution come to life and become such an integral part of the paper. It was also a brilliant first foray into paper writing – to have such a supportive and generous team to work with took large amounts of the panic away from ‘am I doing this right?’ and ‘how does all of this even smoosh together?!’ If you get the chance to work with others for your first paper-writing experience, I super duper recommend it. Especially for when it gets to the final details: formatting, submission, keywords etc etc etc, where I wouldn’t even have known where to begin without the (very) patient guidance of Jocelyn and Dimitri. For a whole host of reasons beyond the control of anyone, the paper came to its final form just a couple of hours before the submission deadline, with three of us sat on overleaf culling, and prodding, and spellchecking on the night of Brexit. The fireworks erupting in the distance just as we agreed it was done added a special kind of bathetic farcical atmosphere to the completion of my first paper.

The paper was accepted with only minor adjustments and we were off to Eindhoven. Except not really, because of “the event”. Instead, we were asked to put together a 10 minute video presentation which would be broadcast as part of the newly styled virtual DIS 2020. We divided the presentation up into chunks and Jocelyn, Dimitri and myself each took a few slides and narrated over them. Recording over presentations is a skill I haven’t had much reason to use since GCSE ICT, but increasingly it’s been becoming an essential skill, and one I am rapidly reacquainting with. You know. Because of “the issue”. Unfortunately, when the time for the conference itself came about, DIS wasn’t particularly interactive and presentations and papers were simply left online for people to interact with as they came across them. I did engage with the hashtag on Twitter regularly and found some new academics to follow, but aside from that, there isn’t much to say on the reception of the paper. I did, to the bemusement of my housemates, however, go rather overboard in the kitchen to make the most of the situation e.g. breaking into the last of my waffles, lovingly made according to the recipe of my fabulous friend’s Oma, to make the Dutch experience come to me. The ultimate power move.

Being involved in the GIFT project in the ways I have, but particularly from being part of VRtefacts, has completely changed certain paradigms through which I approach my PhD. Not only has it provided a grounded example of how integral donation can be as a framing device to bridge the gap between audiences and galleries, but it also offered me an amazing chance to practise multi-disciplinary writing which spanned both of my subject areas (HCI and human geography). I’ve already had opportunities to be involved in other parts of the GIFT project and we have also submitted an article to the HCI Journal special issue on time, exploring how manipulations of time and time-space contributed to the experience of VRtefacts. I’m looking forward to seeing what other opportunities come my way from being part of these papers and practising my shiny new paper-writing skills in the future.

[1] V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77-101, 2006/01/01 2006.

[2] GIFT Project. (2019). GIFT Project. Available: https://gifting.digital/ (Accessed: 8/5/2019)

[3] QSR International. (2018). NVivo 12. Available: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products (Accessed: 01/07/2020)

[4] VRtefacts. (2020). VRtefacts Homepage. Available: https://vrtefacts.org/ (Accessed: 28/05/2020)

[1] https://cdt.horizon.ac.uk/2019/11/04/the-gift-project-2/