post by Kadja Manninen (2018 Cohort)

As we all know, the current pandemic has banned mass gatherings for the foreseeable future. This has meant cancelling academic conferences or trying to deliver them online. When submitting for The British Academy of Management (BAM) conference in February 2020, I was looking forward to an exciting trip to Manchester involving lots of networking with fellow PhD researchers and more established academics. But, as it happens, the virus is still spreading amongst us, and instead of a nice Manchester-stay and sophisticated conversations over fancy conference meals, I was stuck in my study in front of a computer screen for four full days, detaching myself from my laptop only to grab a quick bite to eat.

The postponement of the live conference until 2021 was initially somewhat of a disappointment. But when the time arrived, however, (and perhaps motivated by the long-lagging six weeks of school holidays), I was, in fact, quite excited to usher my child back to school and start engaging with the online event. I was hoping that the symposium could offer me an opportunity to meet other early career researchers specialised in entrepreneurship and/or cultural and creative industries, and also, as my professional background is in event management, I was keen to see how an event that traditionally takes place in a live setting can be adapted into an online environment.

For those of you who are not familiar with BAM (founded 1986), they are the leading authority on the academic field of management in the UK, with a mission of supporting and representing scholars, as well as engaging with the international business and management community. BAM has over 2000 members, out of whom 25% are located outside the UK, and 30% are PhD students. They publish two academic journals; the British Journal of Management and the European Journal of Management Research, and every year they organise the BAM conference, which usually gathers around 900 delegates worldwide.

This blog post is about the doctoral symposium, which kicked off the conference week with a one-day event and was followed by the three-day main conference. I have two focuses with this post. First, I will highlight some key moments from the symposium, which I hope can be useful for other postgraduate researchers. Second, I will discuss the online conference experience from a participant’s as well as an event manager’s perspective.

Symposium highlights

The BAM Doctoral Symposium brought together over 160 participants from all over the world for a full day of Zoom sessions aimed at postgraduate researchers. In the welcome speech the organisers stressed that thanks to the online delivery of the event, the event had attracted more international participants than in the previous years. This was most likely due to the online conference format being significantly more affordable with a lower conference fee and lack of travel costs. The symposium was fully conducted on Zoom, and the programme was split into sessions aimed at both early and later stage PhD students, meaning that we could decide ourselves which sessions were the best suited for our needs.

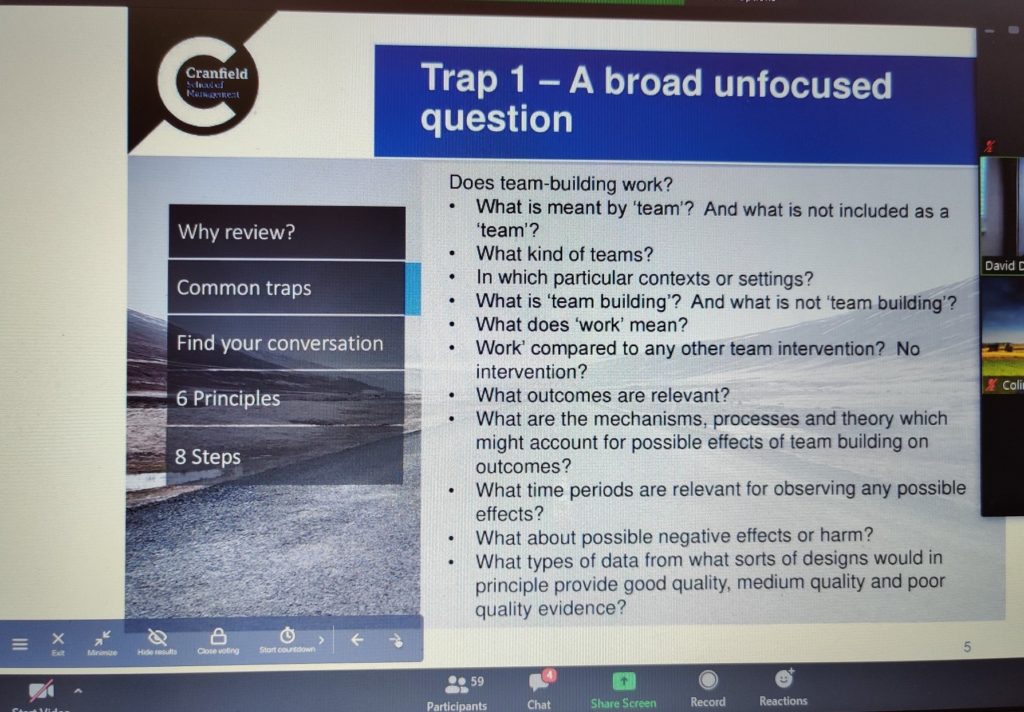

The first highlight of the day was a session aimed at early-stage PhD students, entitled “Conducting a literature review” and led by Prof David Denyer & Dr Colin Pilbeam. Although I’m already starting the 3rd year of my PhD, I have recently been revising my literature review (a never-ending task, I guess…), and therefore decided to join this session. The presenters began by stressing that it’s fundamental to get the literature review right, as otherwise is very hard to justify the research question. Next, they moved on to discuss, among other things, the common traps PhD students fall into when writing a literature review. Out of the seven traps, I found that “the broad and unfocused review question” trap resonated strongly with me. I couldn’t help thinking back to the numerous hours I’ve spent reformulating my review questions in the past year. Below is a useful example of a question that lacks focus and needs narrowing down.

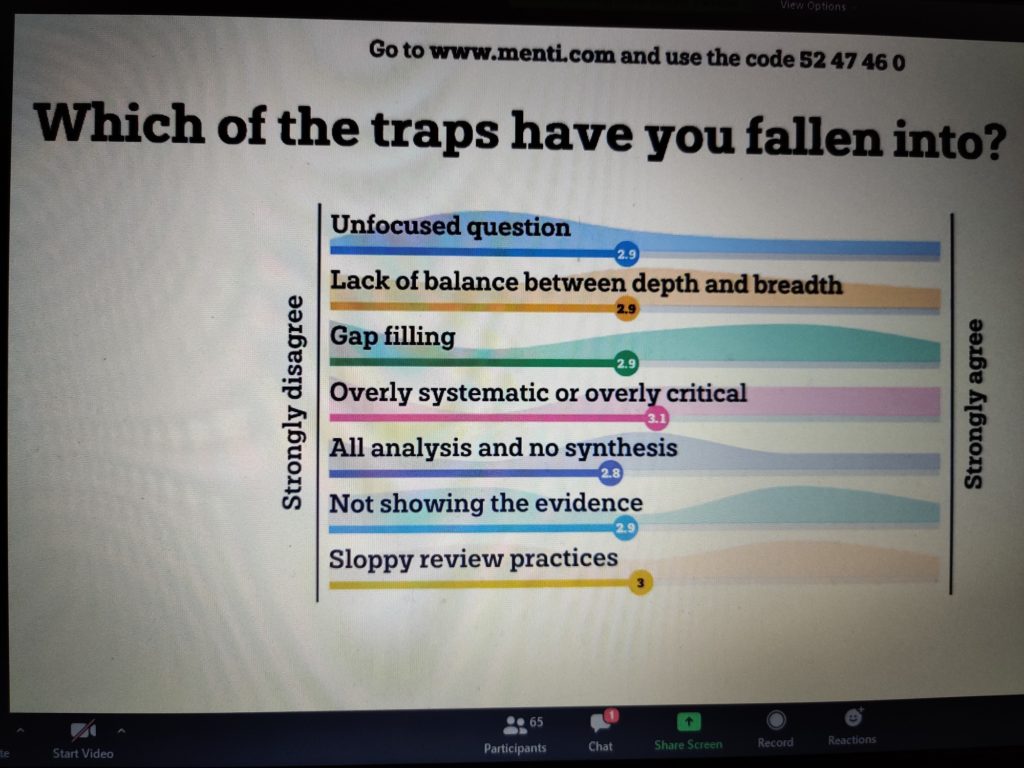

What was particularly good about this session, however, was the presenters’ use of the recently launched Mentimeter software, which enabled them to conduct live polls during the session. Mentimeter has also a free plan that is suitable, for example, for students, and even some of the premium plans are quite affordable. I’m definitely on trying it out with my next online presentation.

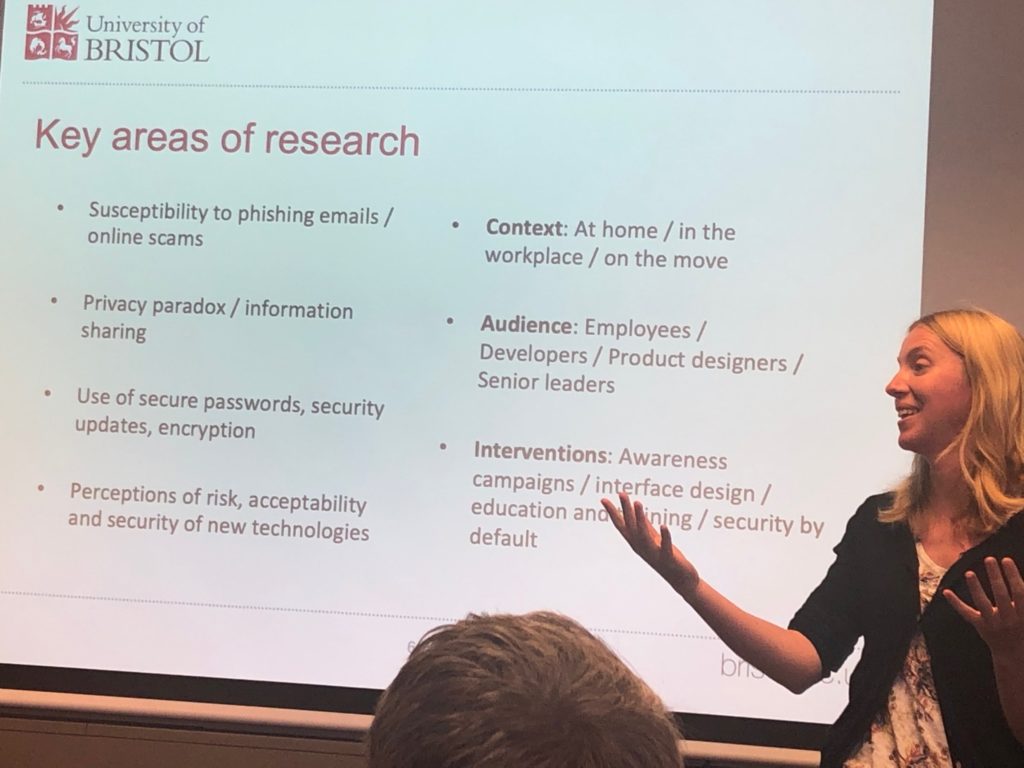

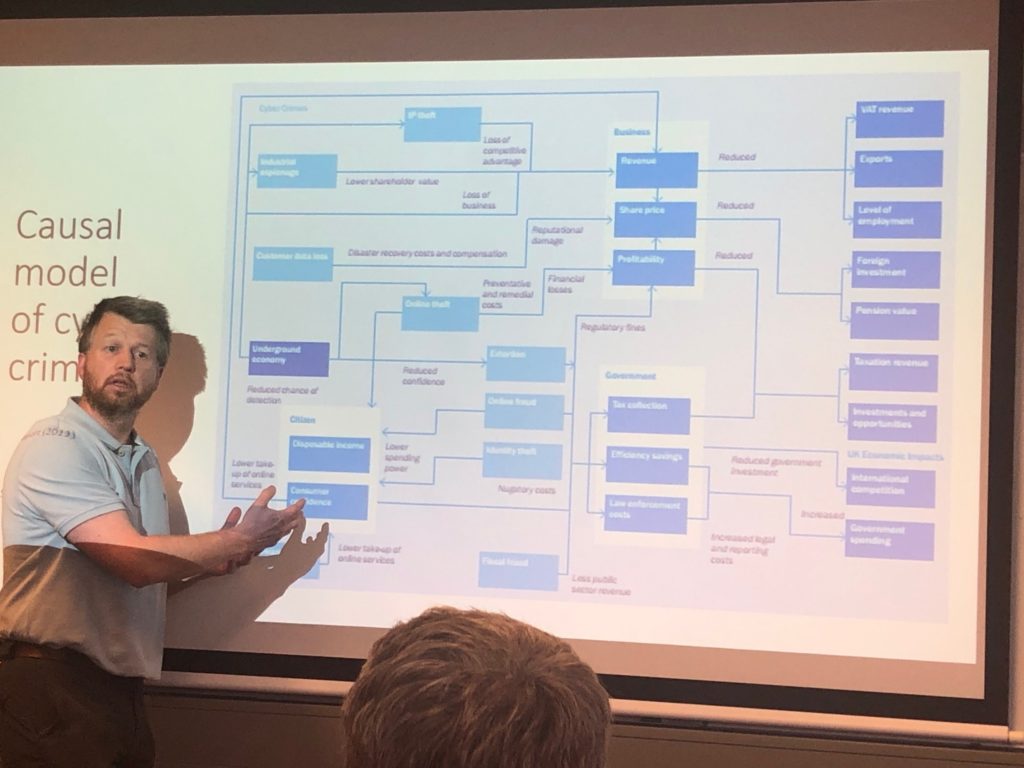

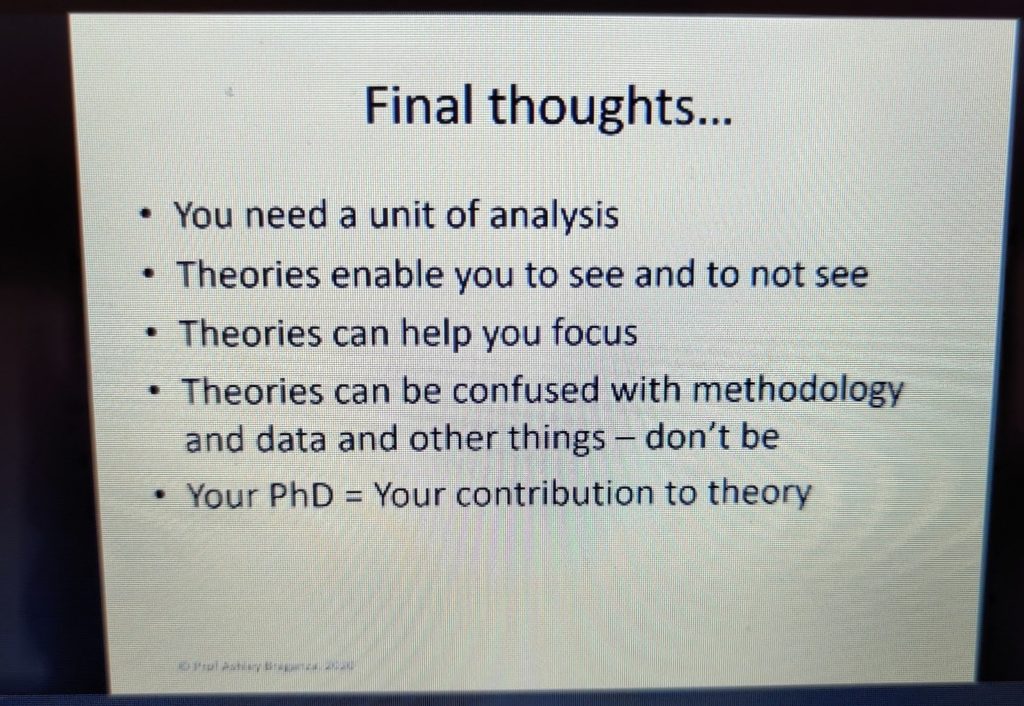

The second highlight of the symposium relates to the perhaps most dreaded question amongst PhD students. I guess each of us is at least once during the PhD journey faced with the question “What is your contribution to theory?” In fact, this happened to me already in my first annual review, and hoping to provide a better answer next time, I signed up for Professor Ashley Braganza’s session entitled “Exploring Theory as a Lens for Research”.

Professor Braganza began his presentation by underlining the relevance of the unit of analysis to doctoral studies. To be honest, I had never asked myself what the unit of analysis in my research was, but I do agree that the question seems highly pertinent and can guide you in the right direction when selecting your theoretical framework.

In addition, he argued that when selecting a theory or theories, you should not go over three theories, but try using a maximum of one or two theories, and the rest can go under the research context. This was somewhat comforting to me, as it is a topic that I have struggled with over the summer while revising my literature review and trying to locate my conceptual home in the broad array of multidisciplinary literature. Again, I think that having too many theories to choose from is very likely to be a common issue for interdisciplinary researchers.

The final highlight of my symposium day was a paper presentation session, where selected PhD students were presenting their research, and were offered a chance to receive some feedback from the audience as well as a senior academic. I decided to watch two presentations in the entrepreneurship track, focusing on female and family entrepreneurship. It was very inspiring to hear of fellow PhD students’ work, and compare their journey to my own. I didn’t submit a paper to the doctoral symposium, as our developmental paper had been accepted for the main conference, and I found that being in the middle of my second phase of data collection wasn’t probably the best time to present findings from my research. I did end up regretting my decision though, and blaming my perfectionism for it, as in fact, it would have been totally fine to present some initial findings from my research. Nevertheless, it was reassuring to realise that others’ papers were nowhere near to be finished or polished pieces of writing. I guess the main advice I can give to other PhD students is that you shouldn’t hesitate to submit to doctoral symposiums, even if your work is still far from perfect. Luckily, I will still have a chance to do so next year.

The online experience

From a technological perspective, everything worked smoothly, and Zoom proved to be an adequate platform for hosting over 160 people for a one-day event. The larger sessions were conducted on Zoom webinar mode, meaning that cameras are only on for the speakers, while everyone else was muted and could asks question in the Q&A section. During the smaller sessions, we were able to have our cameras on and join the conversation if we wished to do so. However, Zoom is not a conference platform as such. This meant that every session had a different URL, and you had to constantly navigate between the PDF programme, where the video call links were, and the actual Zoom app. As I was also taking notes, and occasionally tweeting, the whole experience was quite laborious as it involved continuous switching from one browser page onto another depending on what I wanted to do. I do hope this pandemic and the increased demand for all-in-one virtual conference platforms will motivate companies to develop more user-friendly platforms that can handle large numbers of participants, as I haven’t yet been lucky enough to come across one.

To sum it up, a virtual conference simply cannot compete with the real thing – at least not yet. However, until technology develops enough to provide a smoother experience, it remains the best option we have for maintaining at least some aspects of normality. That said, the main difference between the online and live conference formats was undoubtedly the lack of ad hoc networking opportunities, those random conversations that in real life might take place during a coffee break, or over a conference meal. For instance, we were able to ask questions during presentations on the Zoom Q&A section, but there were no real opportunities to engage in a conversation with fellow PhD candidates.

It is evident that spontaneous digital engagement between people who have never met each other is extremely difficult to achieve in a virtual setting, as it doesn’t occur naturally or without encouragement. However, I do realise that this is only the beginning of what might be an era of virtual events, and the technology for conducting this type of events is developing at a rapid pace. I think that it’s important also that event organisers take the risk of experimenting with different software and try out new ways of structuring their events. For example, and perhaps because of time restrictions, this event didn’t have any time allocated for networking, meaning that 160 participants didn’t have a real opportunity to meet each other. This was not the case during the actual BAM conference, where plenty of time was allocated to networking in custom-made virtual coffee rooms, but as it was not compulsory or moderated, only a handful of delegates made the effort of engaging with others.

From the virtual doctoral symposium experience, I think the main takeaway is that it sparked my appetite for the BAM live conference and introduced me to a like-minded, extremely inclusive research community. As my research basically sits in between arts and business, I remember that last year after participating in the Audience Research in the Arts conference, I did end up feeling a bit like an interdisciplinary alien. That’s why I’m happy to say that with the BAM conference this year I didn’t feel like that at all, on the contrary, I felt like the business and management community was (virtually) embracing me quite warmly. My fingers are tightly crossed in the hope that in 2021, I can take part in the doctoral symposium and BAM conference in person and I’ll promise to be very grateful for every little opportunity for small talk or any form of live conversation.