post by Giovanni Shiazza (2020 cohort)

Meta-Meme, a responsible researcher’s tool for analysing internet memes, is a short position paper and poster my supervisors and I published at the second Trustworthy Autonomous Systems (TAS’24) Hub conference (2024).

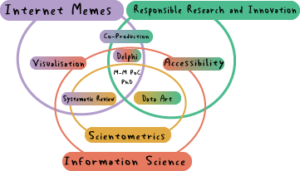

In this short position paper 👆, I establish the grounds for the PhD: Responsible Research and Innovation, Internet Memes and Information Science. I illustrate the theoretical and practical motivation of the project as well as the practice-research gap I seek to help bridge.

In the RRI section, I illustrate how I got to this point, including the AREA exercises and theoretical thinking done on RRI and internet memes. The paper then demonstrates the methodology and its operationalisation into Delphi questionnaires and workshops. The paper concludes with the importance of such a project in today’s AI industry, which is primarily iRRIsponsible.

The purpose of this paper was to publish the grounding and approach of the PhD whilst obtaining feedback and reviews from peers on the specific elements of the research project. Overall, publishing this paper in a trust conference was beneficial and validating.

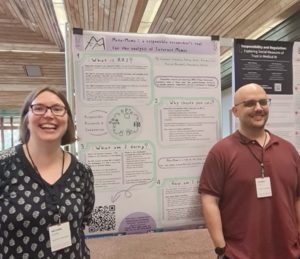

Okay, so then I prepared for the conference, which involved preparing a poster and survey to collect participants with a QR code printed on the poster.

Scanning the QR code (bottom left) leads to a survey to sign up for evaluative interviews as part of the project, widening participation from multidisciplinary researchers and RRI scholars.

Attendees liked the poster; its visuals and colours could draw people in, so the supervisors had further conversations about the project with my supervisors.

My supervisors (proud parents)👆 attended the TAS conference in Texas and presented my poster while I was at the GSE conference, networking and recruiting more participants for the evaluative interviews.

Unfortunately, I could not go to the conference in Austin, Texas, as there was another conference happening in London, the Government Sciences and Engineering Conference, where I went to reach more policymakers and civil society stakeholders.

Preparing the paper

I started preparing the paper months before the deadline by reading and selecting parts of the documents ready for the PhD’s annual progression reviews. This reading was also done with the materials I prepared for the Delphi workshops, which helped me shape the structure and content of the paper. Most of the content of the paper came from annual review documents. There were a few iterations of the paper based on feedback from supervisors to clarify, restructure, cut out and modify specific parts of the paper. Specifically, for this paper, I found it challenging to find the right tone for a position paper, express the background of the PhD without going into too much detail and balance that against the maximum word count.

It was my first time writing a paper with a specific LATEX template (ACM paper template), and I found it challenging to start, but once I started, it got easier to understand. I have to say I do not particularly like using a template, but it made some things easier to do (referencing, paging and structure) but others more difficult (placing tables, images and making the first page of the paper pretty) and others that were just interesting to do (adding images, creating alternative text for accessibility and screen readers). Latex is a tricky system to get used to, but once you do, you will never go back to MS Word.

I decided to include 👆 what Latex calls a “Teaser image” which appears at the start of the paper as a visual illustration/summary of the paper. The image illustrates where the PhD is positioned in relation to the related disciplines and fields of research. For accessibility reasons, I also produced an ALTXT for the image (as per ACM requirements) which is only available for screen readers. Describing this Venn diagram was quite challenging, as many overlapping sections made the description lengthy. This was a complex but necessary and essential step to do in order to allow more people to be able to access the paper fully.

The reviews pointed towards a weak acceptance and minor corrections to the paper. The reviewers pointed to adding some clarifications around internet memes, RRI, more specific inclusions, and more concrete examples. As this is a position paper, no new data was produced to go with the paper, so I could not satisfy some of the reviewers’ comments on adding results and data. The paper also needed to be tidied up both in the writing and visual senses. In the review process, there was no way to ask questions to the reviewers or comment on the reviews; you just had to update the paper to match their comments, but there wasn’t another round of reviews. Of particular importance for my research, the reviewers commended the approach and grounding of the PhD, as methods and the proactive stakeholder engagement focused on common understandings of internet memes, answering researchers’ needs and proactively seeking societal acceptability. I was very happy the reviewers could see this in the paper and the positive comments on the approach and methods.

As this was a short paper, it also included preparing a poster which is included below👇.

In conclusion, I think you should always try to publish something as a PhD student and if your paper is rejected, then use the peer’s comments to shape the next iteration of the project or paper. I know getting a paper rejected that you have worked on for months is soul-crushing.

My advice (based on personal experience) is to take a week or two to process the rejection and the feelings, then go back to the paper when you feel ready to face reviewer 2’s comments with a fresh mind and eyes; chances are you will actually understand the comments and make your research better so that next time you submit a paper you will have a better shot at publishing.