post by Neeshé Khan (2018 cohort)

This Summer School and workshop was hosted by the Kent Interdisciplinary Research Centre in Cyber Security (KirCCS) and School of Computing at the University Kent, the Institute of Applied Economics and Social Value at De Montfort University and International Association for Research in Economic Psychology (IAREP). It took place at Canterbury between 15th to the 17th of July lead by Dr Jason RC Nurse.

As I’m working on accidental insider threat within cybersecurity to examine human factors that trigger this threat, I was keen to attend this event as it would provide an overview of the issues around social engineering and associated forms of crime in the virtual and physical world – broadly sitting within my own research interests. Recent media has highlighted many cases where fraud and cybercrime have resulted from a mixture of social engineering and human vulnerabilities to gain undesirable outcomes including encryption of data to hold at ransom on an organisational and individual level. Whilst there is literature on cyber-psychology linking to malicious insiders and cybercriminals, there is little literature available that takes an interdisciplinary approach to tackle this problem, especially examining this from a psychological, economics, and cybercrime perspective. So the aim of the summer school was to introduce these disciplines and their relevance to be able to better understand this challenge. This was particularly important to me as I believe that all the global challenges being faced by the world today require collective interdisciplinary action to resolve them.

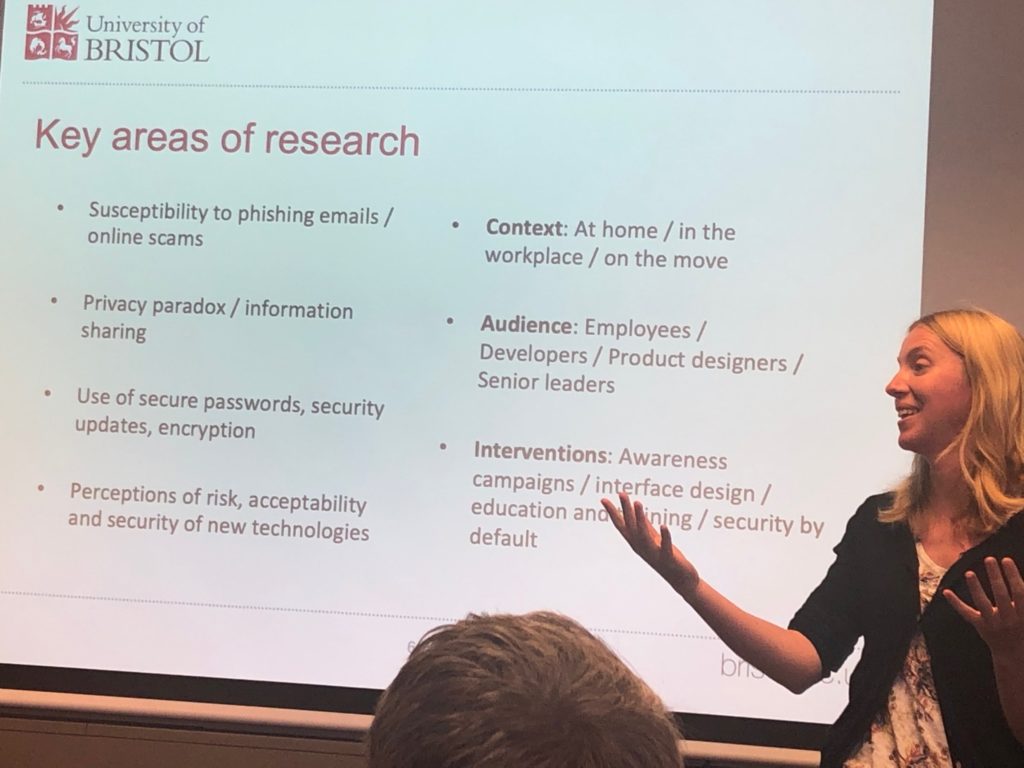

One of the highlights of attending this school was meeting a diverse range of about 40 attendees, which included different career stages within academia, people from industry, diversity in research being pursued and interests as well as diversity in ethnicity, age and academic backgrounds. Whilst most of the projects weren’t similar, it was still cohesive in terms of disciplines and understanding of cybersecurity. This allowed a space where I shared and received ideas and insights about this issue over workshop discussions and group dinners. Presentations were a mixture of academics from various universities including the University of Bristol and the University of Cambridge as well as law enforcement. I hope my notes below are of interest to anyone from psychology, economics, and cybersecurity fields taking an interdisciplinary approach to exploring cybercriminal and victim behaviour and traits, especially those involving malicious or intentional insiders.

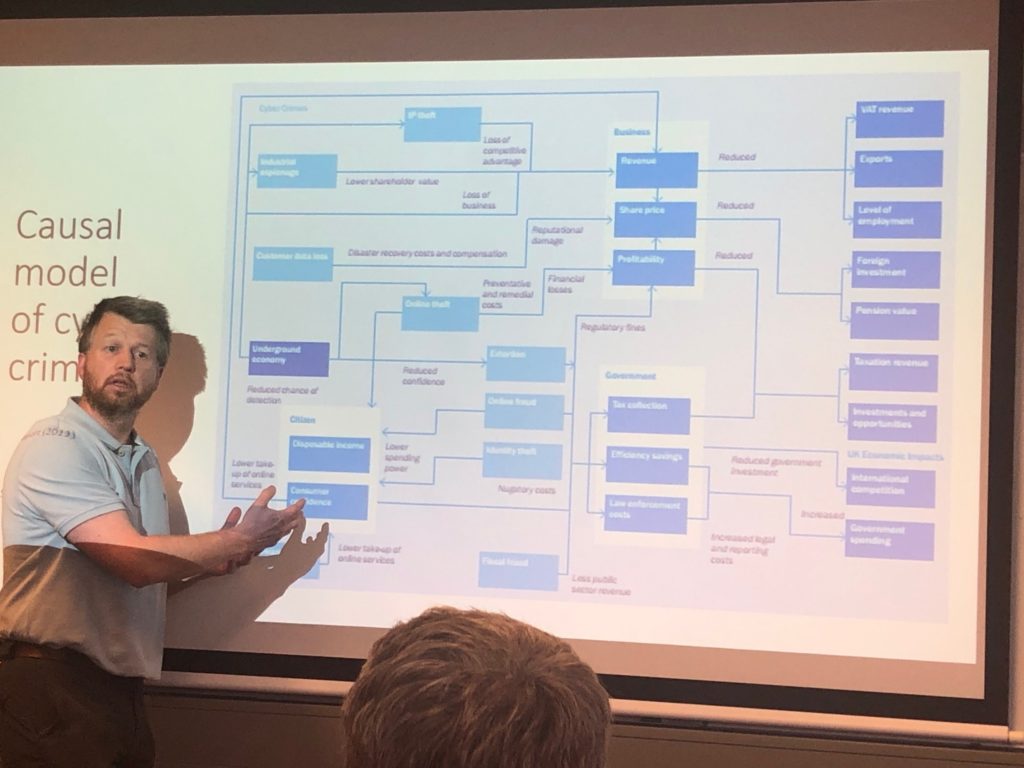

Discussions included how the definition of cybercrime is hard to settle on as it means many different things for researchers, businesses, and individual users. Technology evolving has meant that many of the devices aren’t seen to be within the remit of cybercrime by the general public, for example, cybercrimes that happen through mobile phones or smart wearable devices are seen to be separate from the same crimes that occur through a desktop or a laptop. A way of looking at cybercrime is by categorising attacks that are ‘computer dependent’ (DoD, ransomware, etc) and those that are ‘computer-enabled’ (online fraud, phishing, etc). This can also be categorised through Crime in Technology, Crime against Technology, and Crime through Technology.

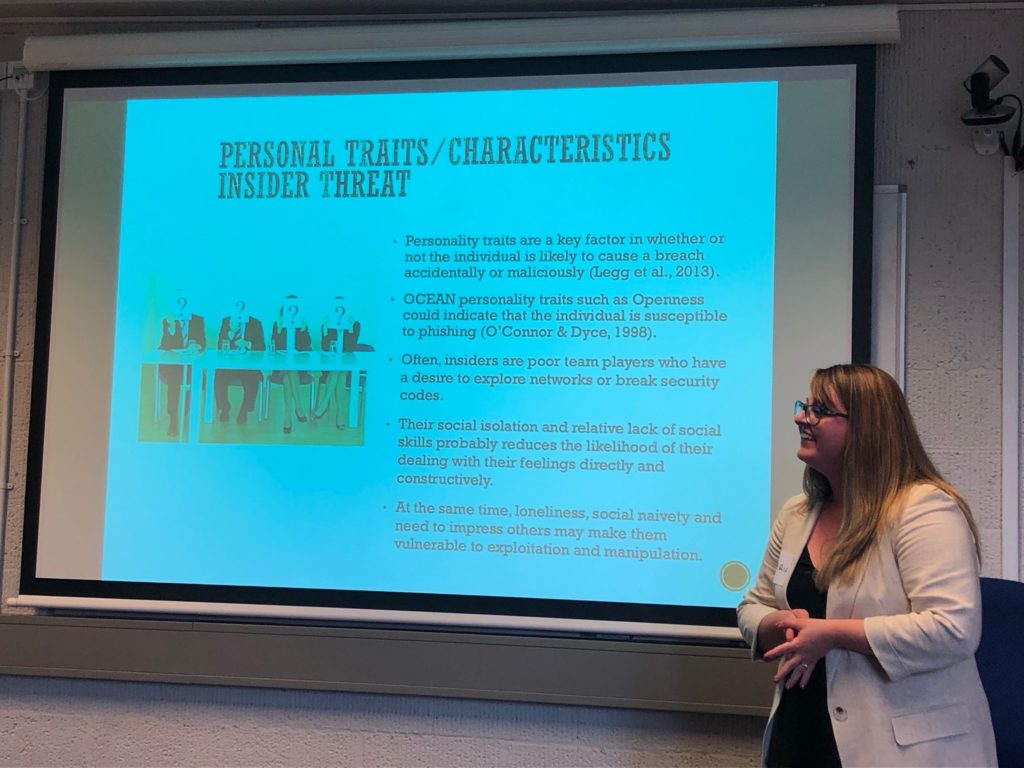

Cybercrime is a big challenge being faced by society and whilst there are numerous different types of cybercrimes, currently, popular ones include social engineering, online harassment, identity-related, hacking, and denial of service (DoS) and/or information. Social engineering and phishing attacks are the biggest attacks that are currently taking place. Cybercriminals are getting better at replicating official documents (less spelling mistakes, logos, branding, etc) and use a mixture of techniques that include misdirection and pressurising recipients to take action. Most classifications of cybercriminals are through using early techniques developed by the FBI’s human behaviour department and include the Dark Triad and OCEAN personality traits. Techniques used to investigate crimes in real life such as ‘method of operation’ (MO) and copycats seem to transfer relevantly well to cybercrime investigations.

Law enforcement believes that in their experience there is a strong link between gender, age, and mental ability and cybercriminals. Children test out their coding skills from lessons in schools to attack websites or online gaming platforms. There also appeared to be a strong link between online gaming habits, mental disorders such as ADHD and hacking. Whilst there are more cybercrimes reported to the police than crimes in the physical world, the task force is still suited for ‘boots on the ground’ than cybercrime. All individual reports of cybercrime are done through Action Fraud and involved cybercrimes that came from someone they knew such as disgruntled ex-partners. Threats included a wide spectrum but the most popular ones included fraud, abuse, blackmail, harassment, and defamation of character.

In psychology, cybercriminals are classified in similar ways to that of criminal profiling in real-world crimes. There is also interest in exploring victim traits since individuals who are a victim to an online attack are likely to be a victim to another attack in the future. When looking at cybercriminal profiling psychological and emotional states are key factors. Various online forums are researched to create a cybercriminal’s profile mainly through the following categorization: language used, attitudes towards work (for example in the case of a malicious insider threat), family characteristics, criminal history, aggressiveness, and social skill problems including integrity and historical background. However, this is challenging as personality traits and characteristics are easier to change online especially for narcissistic personality traits. However there is never a 100% certainty of creating a psychological profile of a cybercriminal, with very little research and involves stereotypical profiles such as ‘white, male, geek, like maths, spends a lot of time alone, plays online games, anti-social traits, etc. Often personality traits associated with ‘openness’ of individuals links to individuals being susceptible online to phishing and other scams.

Most important models of profiling are ‘inductive’ and ‘deductive’ criminal profiling. Inductive is using existing data to identify patterns and deductive is starting from the evidence and building up to the profile (deductive cybercriminal profile model). Deductive method is very popular and is designed by Nykodym et al 2005 but there’s also geographical profiling (Canter and Hammond 2003) that is starting to become more popular as a result of social engineering attacks. Economists are applying ‘willingness to pay’ (WTP) and ‘willingness to accept’ (WTA) models and game theory to ransomware attacks.

Overall, the summer school provided a great platform to create a new network, reaffirmed my understanding of the current approaches being adopted, offered insights to some of the research being conducted, and provided a platform to promote my research.